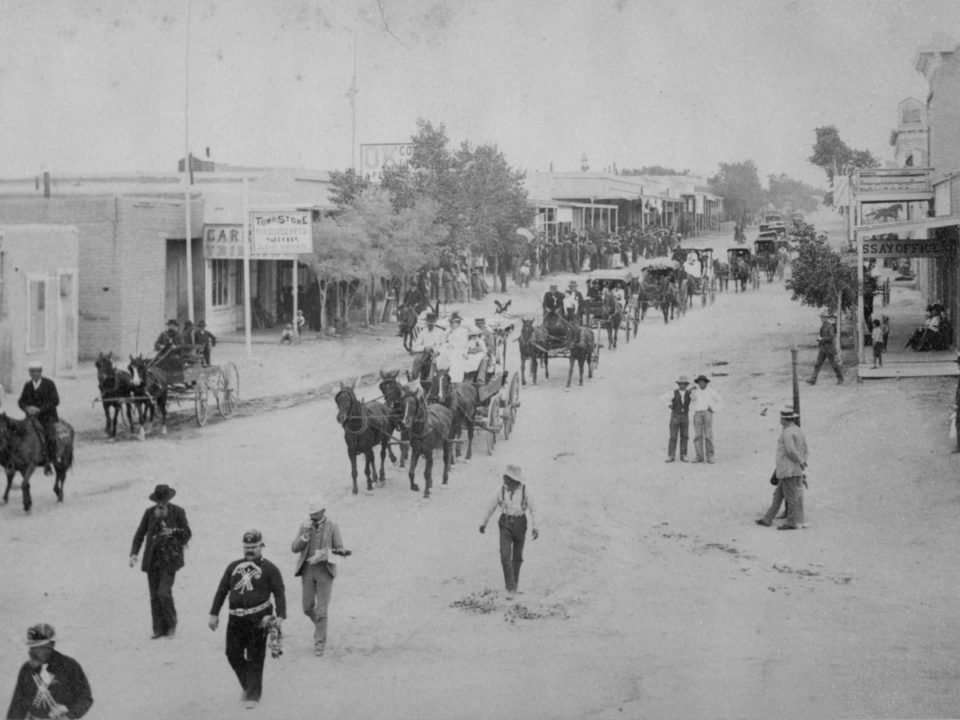

The gunfight at the OK Corral is one of the central stories in American mythology. Good and evil, law and order, such black and white concepts are set against each other with the “guys in white hats” victorious when the dust of the gunfight settles. Even the rogue Doc Holliday emerges as a sort of Robin Hood merely by choosing the right side to fight on. This legend is the backdrop for Oakley Hall’s book Warlock, one of the finest westerns I have ever read.

Every facet of our mythological old West is portrayed in visceral detail in Warlock. Gun fights, fist fights, bar fights, whiskey drinking, stagecoach robbing, cattle rustling, Indian attacks, cavalry, gambling, saloons, ladies, whores, miners, posses, lynch mobs and riots; Hall covers them all. Yet Hall does not portray these common Western themes in the manner of “classic” westerns. Nothing in Warlock is shrouded completely by the reassuring veil of myth for every character is human underneath it all. Still, can Warlock really be called a “revisionist” Western?

It seems every film, novel and Broadway musical created after 1949 and set in the old West gets branded as “revisionist”. Not that this should be a stigma, there are many fine works that reexamine the legends of the old West, but these revisionist Westerns are too often stripped of all their mythic grandeur under the searing lens of their magnifying glasses. Hall’s book Warlock is more careful in its reexamination. Rather than replace fantasy with reality as films like McCabe and Mrs. Miller (again, still a fine film) do, Warlock somehow keeps the legends intact while recasting the heroes and villains as mere men.

It is now accepted that Wyatt Earp wasn’t even Sheriff of Tombstone at the time of the gunfight at the OK Corral, and most likely didn’t even hit anyone in the shoot out itself. Many of the people they went up against were fairly well liked in town while Doc Holliday was by most accounts a murdering sonovabitch. Hall weaves a bit of this harsh reality into his book, but keeps exactly the right bits of fairy tale as well. Clay Blaisedell (Wyatt Earp) struggles beneath his conscience and reputation, but is still the most powerful presence, purest soul and fastest gun in the story. Tom Morgan (Doc Holliday) is a nihilistic, misanthropic, murdering sonovabitch, but his motivations and friendship with Blaisedell might be even more pure than the heroic gunfighter’s soul in their pragmatic honesty. Abe McQuown (Ike Clanton) and his men are not all evil and some are even well liked depending on the fickle mood of the townsfolk. Still, McQuown and his men’s choice of lifestyle and the actions that come with it lead them inevitably into conflict with Clay.

This element of choice is a major theme in Warlock. A man is not evil, but depending on whom he backs and the choices he makes for himself he might find himself on the “bad” side after all. Again, in the world as Oakley Hall sees it, this does not mean that anyone is good or evil, merely that they are forced to play out the parts they have chosen in the big picture. In the macrocosm of the old west, there are robbers and rustlers and there are sheriffs and gunmen. Where a man falls in this dichotomy is his own choice. In Warlock, good men can seem weak and bad men righteous depending on how they follow through on the choices they make.

Morgan advises the noble Clay “If you are out to kill a man, kill him. It is war, not a silly game with rules.” Clay’s response: “There are rules Morg…it is just so.” Oakley Hall does not show one side as better than the other, only that the choice is ours and often such choices can turn out to be far more complex and binding than we may think. Thus Hall is able to keep the duality of good and evil along with everything else that makes American mythology so special while still putting a human face on the whole affair.

Leave A Reply