The A.V. Club, as part of its “New Cult Canon” series, recently published a piece on Hackers. While it correctly pointed to the impossible allure of a young Angelina Jolie’s face, I felt that it largely failed to adequately describe just what makes Hackers so brilliant. I’m sure part of the problem is that any attempt to canonize a movie that, on the surface, seems so laughably bad is no easy task. Still, as I have come to grudgingly admit over the years, Hackers is a very important piece of cinema that, along with Blade Runner, is perhaps the most perfectly realized film vision of just what “cyberpunk” actually is.

Cyberpunk, a science fiction genre that rose to prominence in sci-fi novels of the 1980s, is a mythological worldview that attempts to deal with our increasingly technologically dominated society. It is a mythos set in the near future, in a world full of megacorporations, urban sprawl (and, importantly, decay), and artificial intelligence. The lone individual is set against this, alienated in a sea of humanity, they must rise up using the only skills that matter: their ability to manipulate the technosystem.

The degree to which these “hackers” actually exist matters no more than who shot first at the OK Corral. Our Western mythology (which I have written about before) says the Clanton’s shot first, our cyberpunk mythology says hackers can work magic by typing furiously at a keyboard in front of a rapidly changing GUI.

Not only are their skills legendary, their motivations must ultimately end up heroic (or, at least, some form of chaotic antiheroism considering the morally relativistic cyberpunk universe). The A.V. Club article managed correctly identify what makes the “hackers” in Hackers tick:

That combination of prankishness, resentment of authority, and moral relativity are all still present, as is the idealist impulse to break whatever shackles are holding us back and change the world—or, if that doesn’t work, just blow it to smithereens and start again, like the ending of Fight Club.

However, it undercuts the power of the film for the A.V. Club article to focus too deeply on the real world parallels of this. For all their manifestos and noble speeches we all know that real world hackers are really just amoral entitled assholes who think they can take what they want because the are stronger than the rest of the population (at their particular skill set). Which, is most likely what the real Wyatt Earp was like, although that is not the part of that legend that we print.

Like the best classical westerns, Hackers is working on a mythological level, and thus, “printing the fact” is anathema to it (perhaps that would make it a dreaded “revisionist” cyberpunk film?) The young people in Hackers really believe in the nobility of hacking the planet (which in this case could merely mean tearing down the existing system) just like they really have the ability to work magic on their antiquated technology like few others can.

Much has been made of how supposedly laughable it is that the hackers from this film were so impressed with a 28.8 modem. However, technology will always improve; a hacker will simply make the most of what they have. In fact, it is even a hacker badge of respect to cast their spells with outdated technology (just look at Amadeus Cho from the Marvel Hercules comic book–he can hack just about anything using only a game boy and you don’t see people snickering at him).

I’ve said a lot about that special something that makes up the mythological framework of the cyberpunk genre, but how does this film in particular capture this? It’s a tough question to answer considering there is nothing overtly brilliant about Hackers at first glance. The dialog is cartoonishly bad/superficially contrived in places, and the whole thing reeks of megaplex trash that should be forgotten within weeks of its release.

The reasons it was not forgotten are many, but the easiest to pick up on is the soundtrack. I’m a sucker for music in film, and the right song at the right moment will automatically elevate a film in my eyes. For example, I honestly am not sure how much of my claim that Tarkovsky’s The Mirror is my favorite film of all time is due to its breathtaking use of Bach’s opening chorus to the St. John Passion in the final scene. Regardless, they couldn’t have picked a better song than Orbital’s “Halcyon and On” to open the film. I could go on and on about how great this song is (or, at least, the opening of the song), but I’m sure it will probably turn up on a future Minor Key Monday. The rest of the soundtrack is just as good. Prodigy might be a bit too rockish for me (guitars have no place in electronica), but for a film made in the 1990s with a popular music soundtrack, the music has aged VERY well. In short, the soundtrack (at its best moments) captures exactly the kind of feelings that I went on and on about in my post on the Autechre song “Bike.”

The costume design is another highlight. The kids in the movie, for the most part, dress like the customers who shop at a special Hot Topic for androids wished they looked like. I’ve wanted an armored up leather jacket like Crash Override wears since I first saw this movie. And hell, rewatching it for the umpteenth time recently I was reminded that Cereal Killer (pictured above) really had pretty good style. Couple this with their inexplicable penchant for constantly wearing rollerblades (perhaps a nod to the cyberpunk theme of body modification) and you’ve got a group of really cool looking protagonists.

And yet, the soundtrack and costume design only scratch the surface. The real genius of the film can’t be defined, it is in the little things. The fact that the opening flashback scene has the only non-diffused sunlight in the film is important. Most of the film seems to take place either at night, or under a smog covered golden hour haze. The world of cyberpunk derives much of its mythic power from its pre-Ragnarok temporal position. It is an old world of fading light, night is coming, and death with it, but it is not here yet. It is all the more resonant for being our near future rather than our distant future. Ragnarok is coming, and sooner than we might think. Perhaps the most powerful image from Blade Runner is the simple shot of the setting sun from within the Tyrell Corporation and all that it suggests. Hackers is pervaded with the same orange glow, and I would be surprised if it were not influenced by Blade Runner.

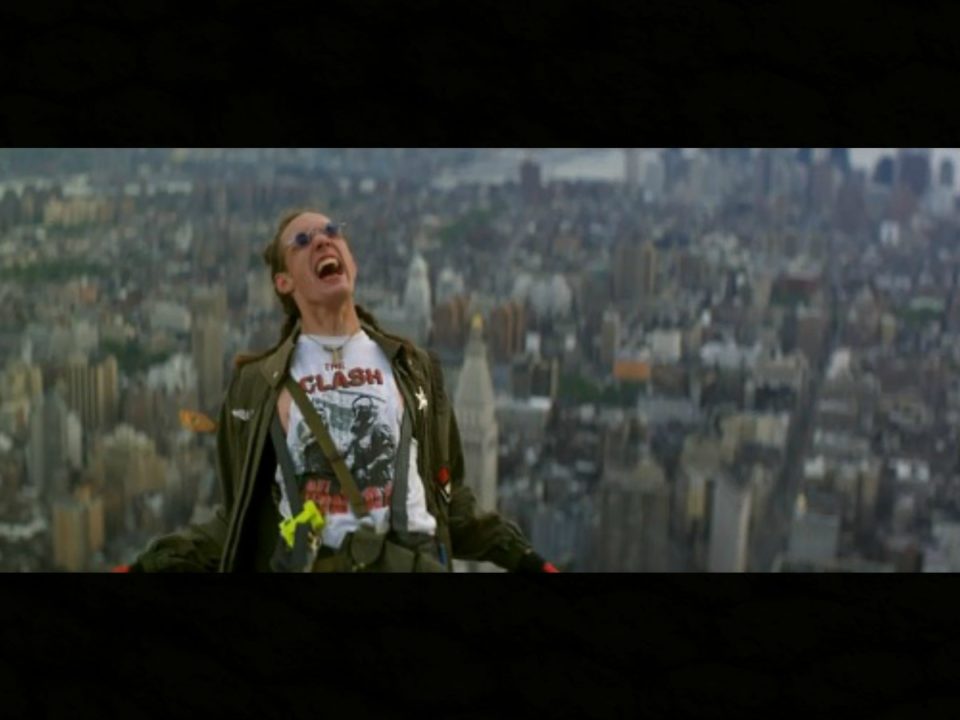

The New York City setting is also important. Tokyo is the megapolis of the future, New York City is the megapolis of the present day, shifted to the near future by the production design that fills the old and decaying city with hacker technohavens. There might be no need for the hackers to do their hacking from the top of the Empire State Building (as the sun sets), but it is an important image that takes us to the very top of the city like something out of one of Ayn Rand’s wet dreams. And then there is the sequence where hackers from around the world use their shared technical expertise to break through their societally imposed exile and unite to hack the planet. It’s an obvious setup, but it works within the mythological context of the film nonetheless.

Does Hackers deserve to be mentioned in the same breath as previous My Favorite Movies by directors like Bresson and Dreyer? Probably not. Is it a complete success anyway on its own terms? I would have to say it just might be. Besides, let’s not forget that Hackers features the sight of Angelina Jolie’s face back when she still had cheeks.

8 Comments

I WANT TO GO TO THE SPECIAL HOT TOPIC FOR ANDROIDS. I demand to know where this special Hot Topic is!!!

You can’t hack a Gibson.

AMADEUS CHO! YES!

Also, were you aware that it is impossible to hack a Gibson?

“…their motivations must remain pure…”

That statement doesn’t reflect my memory of the original hackers in William Gibson’s CP works. The central characters were working for hire, or to improve their station in life; I seem to remember off-hand references to idealists and terrorist as second-rate hackers.

When Hollywood absorbs and destroys a genre, they remove the original motivations and plug in populist morality. It appeals to the meat of the bell curve and sells more tickets.

Yeah, pure wasn’t the right word (even with my “or at least mostly pure” addendum). I just edited the wording of that section to try to get at what I was trying to say, but it’s still a little off.

Basically real world hackers just want to justify why they deserve to pirate media. That’s not so much “un-pure” as it is thoroughly un-heroic. I was concerned that the A.V. Club article, by drawing real world parallels to the characters in Hackers, would bring them into the realm of the mundane.

I’ve only read the Sprawl trilogy by Gibson (a long time ago), and to be sure the characters in this movie are more idealistic than most of his antiheroes, but there is still that urge to foment chaos present in this film that helps.

I think it’s a good point that the idealists should be thought of as second rate hackers. The clips from the Hacker manifesto, and various speeches about “freeing the information” ring a little false (in a merely providing convenient justification way) to my ears in this film.

I’m afraid Sweet Jonny B firsted you on Gibson hacking knowledge bombs. Also, HACKERS IS DEADLY SERIOUS AND NO ON IS ALLOWED TO MAKE FUN OF IT!

I’m afraid their clothes only look like what the androids who shop at the android Hot Topic WISH they looked like. Android Hot Topic is, unfortunately, still pretty weak sauce.