Here it is the end of January and I haven’t posted anything all month. Since I try to get at least one post a month in, I decided to go ahead and cheat (instead of actually writing something new!) and post an essay from a research project I did a few summers ago. I tried to cut most of the boring stuff out, basically you get a fair amount of history on Die Brücke group of German Expressionists and Norwegian Black Metal, along with some conclusions on what an examination of their history has to say about the merit of genre itself. So go ahead and keep reading if any of that sounds interesting. If not, sit back and wait for my upcoming Tolkien Fan Fiction, because this is a long one!

INTRODUCTION

The goal of this project is to gain an understanding of the twofold nature of artistic movements (genres); that is, how the same characteristics that allow artists to reach their creative peaks eventually will lead to the death of the genre they helped create. Imitation of what has come before, while essential for the refinement of an idea, will lead to derivative sterility by its very nature. Genre (a set of stylistic limitations set by the creator of the genre) represents both a way for art to break boundaries of what has come before, and a creation of new boundaries to hamper its continued development. It is this duality that I am most interested in.

In an attempt to understand this, I will look at two different genres of art, specifically painting from the Brücke School of German Expressionism, and a modern genre of music, Black Metal, which is strongly expressionistic in its style. Both genres fall within the wider category of Expressionist Art, and therefore are very useful to compare with each other. By analyzing these two artistic movements, an understanding of the possibilities and limitations of their respective genres will become clear. With this understanding something can hopefully be learned about the strengths and limitations of genre in general.

EXPRESSIONISM

It is important to start with a working definition of Expressionist art. This task is not so simple because the word “Expressionist” can be used to define a broad spectrum of the art world.

Expressionist art is not a new idea, though the term “Expressionism” was not used until 1911 (The Concept of Expressionism, 5). Indeed, “Expressionism in the broader sense is a timeless phenomenon in art. It is found among the Pacific islanders and the Aztecs, in Africa and in Gothic cathedrals, in medieval manuscript illuminations, in Grünewald and El Greco” (Art of the Twentieth Century, 54). And in 1919, Herwarth Walden stated in an issue of Der Sturm (an important expressionist newspaper of the time) that “Expressionism [was] a world movement, of the universal spirit of feeling, linked with creation” (Expressionism in Art 76). Yet most people think of Expressionist art in its narrow sense, as an artistic movement centered in Germany during the early part of the twentieth century. I will be looking not only at the broad definition of Expressionist art, but also at two artistic movements that arose from it.

Expressionist art is not concerned with the everyday obvious appearance of an object; it wants to represent the true nature of a thing. To the Expressionist, each object hides its true essence beneath a shell of normality. The most common method of portraying this “deeper reality” that all objects possess is to distort their forms. Disproportionate bodies and twisted lines give rise to a new outlook on the world, often a cruel and angry world (though this is by no means a defining characteristic of Expressionist art). These images, teetering on the brink of abstraction, confuse the viewer; “Surely this could not be further from reality,” they say, yet the image often rings truer than the world they live in.

This technique of distorting the image is nothing new. Look at how similar the giant stone faces of Easter Island with their distorted features and proportions are to what one would see in a German Expressionist woodcut of the early twentieth century.

Yet distortion of the form, while one of the most common means of reaching the expressionist ideal of capturing the true nature of an object, is not the only way to make Expressionist art. Abstract Expressionism, for example, does away with form altogether. In its Expressionist quest to reach ultimate truth about the world that lies just beyond our senses, the Abstract Expressionists condense their art to the purest forms of color and shape. Simple distortion is too closely linked to the obvious everyday world that we see about us; the Abstract Expressionists want to go further in their quest for truth, further until the form is lost. The emotive possibilities of color present the Expressionist artist with an incredibly diverse toolkit with which to capture their vision. the expressionist painter Emil Nolde once said, “Yellow can paint happiness and also pain…Every color harbors its soul within, delighting or repelling and inspiring me” (Expressionism, A German Intuition, 35). This view of color was very different from teh way traditional artistic styles viewed color.

And still, distortion of form, pure abstraction, and emotive use of color are all merely mediums within which the artist works, they by no means define “Expressionist art”. Any art that seeks to portray a thing beyond momentary impressions and everyday appearance can correctly be termed Expressionist, at least in some respects. The styles I have listed above are simply some of the most popular in the past hundred years.

Now that an understanding of Expressionist art in a broad sense has been developed, I can more easily look at and attempt to understand some of the genres that arose from it. For I am not so much concerned with how an overarching theme such as Expressionism exists, but how Expressionist art gives birth to various narrow genres that are eventually stifled by the boundaries they set for themselves. Is “genre” too narrow a field for creative output to flourish? Or does “genre” allow the artists to focus their vision, and eventually perfect it? Keep these questions in mind as you read on.

BRÜCKE

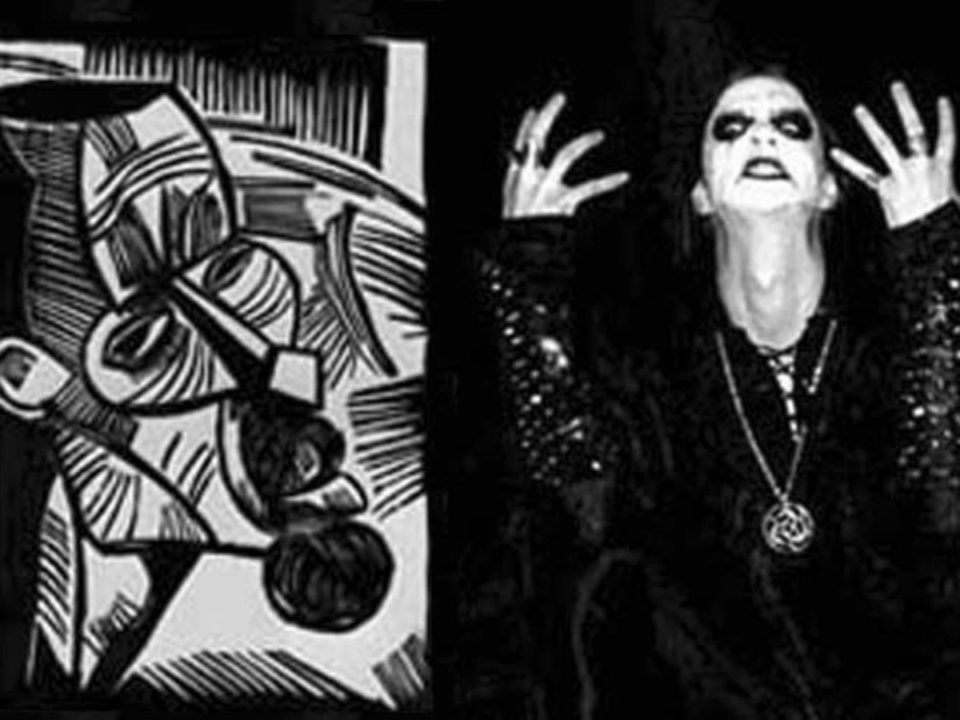

The first of the two genres I will look at is the Brücke School of German Expressionism. Possessing many of the trademark qualities that would become synonymous with Expressionism, the Brücke artists (formed in Dresden in 1905) were among the first artist’s making wholly expressionistic work (Expressionism 34). This is not to say the Brücke school was the only, or best example of early twentieth century expressionism; they are just the group I have chosen to examine in this paper (for their unique style as well as their similarities to the Expressionists in Black Metal). The founding members of Die Brücke were Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. Later Max Pechstein and Otto Mueller joined, along with Emil Nolde for a time (Art of the Twentieth Century 52).

German Expressionism during the turn of the century was very much a movement of rebellion. In his book Expressionism, Frank Whitford states that, “to be an Expressionist was to be young in an old and tired world. It was to believe in the bankruptcy of society, the idiocy of the masses and the falseness of the generally held picture of the world” (18). The Expressionists did not want to merely capture an impression of reality as the Impressionists did; they wanted to go further and get to reality’s inner core. Theirs was an art meant to lay bare the falsity of the world around them, to discover “truth” as unpleasant as it may be. Many people had ugly “souls”, so the Expressionists distorted the figures in their paintings to the point of grotesqueness. The city and industrialized world were not viewed with the same enthusiasm as the Futurists (for example) saw them, so they painted sinister cityscapes saturated with unsettling emotion. Whitford adds that, “expressionists saw [the city] as a black, huge and unnatural environment, which perverted and depraved” (Expressionism 119). In their drive to capture the truth, the German Expressionists came to know the city and industrialization as the furthest things from the purity of the countryside.

The painting style of Die Brücke had many of the techniques which Expressionist art has displayed over the centuries (distortion of form, vivid color, etc.), and these techniques often gave the paintings a “crude” look:

Many critics, most often non German, are disturbed by many aspects of Brücke painting and are inclined to write it off as crude and immature, the result of a serious lack of talent. This is understandable. The Brücke painters were not natural virtuoso performers… sophistication was not their aim, nor did they seek for a form of painting which would be easy on the eye. (Expressionism 120)

When compared to their French counterparts, the Brücke artists were often dismissed as amateurs. Yet, “as far as art was concerned, its members hoped to compensate for their lack of training and experience with an excess of zeal” (Expressionism 38).

The Brücke group worked in a closely-knit collective of artists, with Ernst Ludwig Kirchner their self-proclaimed leader. Yet it seems Kirchner’s influence and leadership within the group was not due completely to his painting. While his grandiose notions of what the new German art should be were a profound influence on the young members of the Brücke, Kirchner’s talent at reproducing them on the canvas did not develop so quickly (Expressionism 39). Again, this is not to discredit Kirchner’s role in the development of Die Brücke, for, while:

In 1905 Kirchner’s work lagged behind his ambitions, his ideas, developed by two years of intensive thought and fairly serious reading, plus a wealth of visual experiences, were maturing and becoming very definite and he transmitted them to other members of the Brücke. (Expressionism 40)

Also, this is not to say that Kirchner remained artistically behind the other Brücke artists, for his later work is easily among the greatest of the Brücke paintings.

Die Brücke worked in a communal atmosphere, sharing ideas and techniques among each other. This atmosphere enabled them to progress very rapidly in their technique, a partial reason for their meteoric rise to the cutting edge in the German art world.

Yet this environment of collaboration and shared ideas was not to last. Each artist eventually wished to express his own voice, to go in a new direction. They felt restricted by the genre that they had created. Emil Nolde was one of the most obvious examples of this, staying in the Brücke only for a year and a half (Art of the 20th Century 49). Each artist, during his time with the Brücke, had “become aware of his own idiosyncrasies and intended, more than ever before, to assert them” (A Dictionary of Expressionism, 35).

A major source of conflict during the final days was the increasing popularity of Pechstein, which seems to have angered Kirchner who had always been the unquestioned leader of the group. Eventually Pechstein left, showing the extent to which a rift had formed between him and Kirchner. Kirchner obviously resented Pechstein’s growing popularity (Expressionism 119). And soon, due to a desire to move on, or petty bickering amongst themselves, Die Brücke had disbanded.

BLACK METAL

The other genre that I will look at is called Black Metal. An obscure style of music that arose in the early 1990s, Black Metal is very closely tied to expressionism. I will specifically examine the second wave of Norwegian Black Metal that lasted roughly from 1991 to 1996. Of course this is not to say that Norwegian Black Metal was the first or best form of Black Metal. Many countries, including Poland, France, Greece, and the United States, had active Black Metal movements at fairly early dates. Also, the music existed in various primitive incarnations prior to 1990. Like Expressionism, it is tough to identify the exact point of origin for Black Metal, but few can doubt the importance of the Norwegian scene.

A style that was as much a reaction to the sterile and oppressive Scandinavian society that its youthful creators lived in as it was to traditional music, Black Metal is immediately displeasing music. Black Metal creates immensely expressive songs out of the most minimal of elements in the same way the Brücke artists crafted their haunting images from the simplest forms. Instrumentation is purposely recorded with as much distortion and white noise as possible, all while playing only the bare minimum of notes required for any kind of melody.

From these sparse elements music emerges that is at once repulsive and mesmerizing. Unlike other popular music, the focus is not on what notes are played, and how polished the composition is, but rather on what is not played. In the right mindset, the beauty of Black Metal emerges, like a copy of a song thousands of years old, its sound warped and degraded through the years until naught remains but a dim memory of that which once was. It is not to be listened to as background music; it takes a great effort to focus on the song, to see past the screams, noise and repetitive simplicity.

“I cannot fall in love/Love is for them/Lusting for the sky” sings/screams Varg Vikernes of Burzum. Channeling their extreme alienation into various forms of sorrow, anger and hate, the Black Metal musicians wanted nothing to do with anything outside their “inner circle”. A strange sort of nihilism emerges, dominated by a hatred of all that is in this world, yet still possessing a longing for times past. Hopelessness and hope emerge from the same shredded music.

The self proclaimed leader of the Black Metal inner circle was Oystein Aarseth, or as he was known in the Black Metal scene, Euronymous. While his band Mayhem did not produce any work of great import until 1993, after most of the important Black Metal albums had already been made, Euronymous turned out to be the inspiration for many of the trailblazing bands through his ideas. In interviews, most all of the important bands from the early nineties (Emperor, Immortal and Darkthrone to name a few) give Euronymous credit for influencing their move into the realm of Black Metal.

Often these bands would start as Death Metal bands (the reigning style of extreme music at the time) and then move on to become Black Metal bands. The change was drastic and the difference in both music and attitude immediately obvious. In an early interview Darkthrone display this attitude with both their contempt for their older “Death Metal” style and an unbridled enthusiasm for their new Black Metal direction:

We are the new Darkthrone. We deny old Darkthrone stuff. We formed in 1991. All has changed. Unholy black metal and satanic poetry are us. We hate death metal and trendy scene. We will not be part of it. To isolate is what we must do to make black metal pure! If you want to stop an eventual black metal trend; stop writing a zine and isolate! We, the hordes of Satanas are not trying to save everybody, neither do we want to spread our dark knowledge. We are no missionaries! Stay dark and occult. We have fired members of our band and we have nothing to do with old Darkthrone. We have boycotted all live stuff, we do not wish to play with any trendy band. (Dremonium Aeturnus zine #1)

While their Satanic posturing was simply hot air designed to infuriate the moral majority, the attitude of isolation, of the Black Metal musicians against the world, was taken very seriously. The Black Metal musicians realized that if they were not completely serious with their ideological outlook then the music would fail, so they set out to make something far more severe and unrelenting in its delivery than anything that came before (Lords of Chaos, 32). In a 1992 interview Euronymous states:

There is an ABYSS between us and the rest. Remember – one of the [Hardcore – a style of punk music] rules is that [they] must be open-minded (except for themselves), so we must be careful and avoid being open minded ourselves. (Orcustus Magazine, 36)

Black Metal wanted nothing to do with any part of the society which its musicians felt that they had no place in.

Such an uncompromising attitude fit quite well with music that no one seemed to want to hear anyway (copies of demos were often distributed in the hundreds worldwide). Like the Brücke, the Black Metal musicians intended to “produce works of art for the sake of creative expression and appreciation alone rather than for the delectation of the cultural elite” (Brücke, 17). Yet this fiercly individual and elitist attitude also served to create a very narrow vision of what “true” Black Metal was.

Unfortunately, with such a narrow definition of Black Metal, the genre had largely been explored after only a very short time. Also, like the Brücke artists, the Black Metal musicians fell victim to petty bickering over who was the leader of the genre. Yet the fighting among members of the inner circle was taken to the extreme, and within four years many of the founding members of the Black Metal scene were either dead or in jail.

CONCLUSIONS

It is interesting that both the Black Metal musicians and the Brücke painters sought to express the same ideas in the same ways independently, yet both genres ended the same way. So, what were the reasons for these genres dying out, and what do they tell us about the lifespan and worth of other genres? These are the questions that I will now focus on.

The most important reason for the death of these genres is that they simply ran out of ideas. After a certain amount of time, there were no new areas to explore that remained within the stylistic limitations set by the creation of the genre. The more limitations that a genre has, the shorter its lifespan inevitably is. A style like Black Metal, so full of restrictions on what the music should sound like, will end up dying out very quickly. Unfortunately, many of the Black Metal musicians are still trying to create in a genre where any new creations have been exhausted long in the past.

Yet in most cases, the artists recognize when they are creating works of lesser substance, and when the genre is exhausted. In the case of the Brücke, the artists moved on to new genres, to experiment with new outlets for their creativity.

Another factor that is perhaps more relevant in the case of Black Metal and the Brücke is that they were fairly youthful styles. The rebellion and extreme nature of much of their art was very much a thing of youth. As the artists mature, and mellow with age, the confrontational nature of their work will become much harder to sustain. However, this is a fairly specific reason for the death of a genre, and secondary to the exhaustion of a genre’s possibilities.

So what merits does genre have? If it will only end in sterile derivative art, why should artists continue to work in genre? For one, it focuses the artist’s creativity. No one constructs a masterpiece on the first try, and working within the confines of genre gives the artist something manageable to work with. Genre allows for the revision necessary for perfection.

Thus genre is an invaluable tool for the artist. Without genre, it would be nearly impossible to reach the highest regions of perfection that define so many masterpieces. But it is essential that the artist recognize when the genre has peaked, and when it is no longer a benefit. Often by the time the public has recognized a genre, it is already spent. While genre is temporary, the ideas behind it are eternal. Genre is merely a method for reaching these eternal truths.

Bibliography

Brücke. New York: Andrew Dickson White Museum of Art, 1970.

Cheney, Sheldon. Expressionism in Art, Rev. ed. New York: Tudor publishing company, 1948.

Dremonium Aeturnus, Issue 1, 1991.

Expressionism, A German Intuition 1905-1920. New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 1980.

Moynihan, Michael and Didrik Soderlind. Lords of Chaos: The Bloody Rise of the Satanic Black Metal Underground. Venice, CA: Feral House, 1998.

Muller, Joseph-Emile. A Dictionary of Expressionism. Great Britain: Eyre Methuen LTD, 1973.

Orcustus, Issue 2, 1992, pg. 36

Walther, Ingo F., ed. Art of the 20th Century. New York: Taschen, 1998.

Werenskiold, Marit. The Concept of Expressionism: Origin and Metamorphoses. Translated by Ronald Walford. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1984.

Whitford, Frank. Expressionism. New York: Hamlyn, 1970.

Comment

A very thoughtful and insightful paper. I remember very specifically the first time I started to view black metal in this sort of context. Prior to that time, I enjoyed bands like Emperor and even Burzum, but I could never get my head around why Darkthrone sounded the way they did. My enjoyment up to that point was couched in a mode of analyzation that black metal had all but dismissed. Then on my way home from a visit to you at KU in ’99, it hit me as I listened to “Transilvanian Hunger” on a CD you had burned for me. I started to think of all their aesthetic choices as a mode of expression, rather than trying to judge it based solely on technical merits. Anyway, great job!