World War II has always fascinated me. There are all kinds of interesting things about “The War of Nazi Aggression”, but I think the thing that really appeals to me is that it was the first war to truly utilize modern “combined arms” tactics. The proper integrated use of armor, air-power, artillery and infantry was developed and perfected in WWII making the tactical side of things a far different beast than the “storm the trenches” slaughter of WWI (not that there weren’t plenty of senseless tactical decisions in WWII).

This emphasis on combat tactics along with the overall strategic thinking has endless appeal for that part of every young man that secretly just wants to come up with a brilliant plan to win anything from a snowball fight to the capture of a bridge. War is no game, and I’d never want to risk my neck even if it was, but looked at with hindsight, the military decisions made at all levels of battle in World War II offer a wealth of fascinating tactical and strategic dilemmas if you are into that kind of thing.

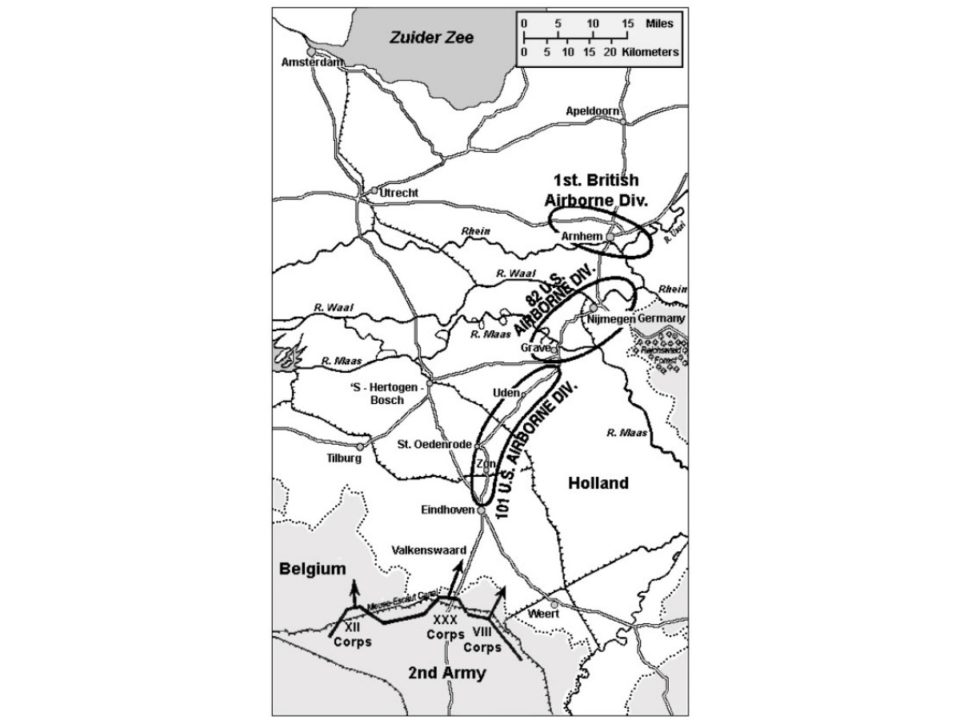

With that in mind, I wanted to take a moment to look at one of my favorite WWII operations, Operation Market-Garden. Perhaps most well known from the book and movie A Bridge too Far, Operation Market-Garden was the code name for the plan to send 30,000 paratroopers along a 60 mile corridor of highway in the Netherlands to capture key bridges in order to remove the last of the major natural barriers (namely, the Maas, Waal and Rhine rivers) into Germany. The paratroopers were to hold the bridges while a massive concentration of armor would break through the German front lines and race up the narrow highway to reach the Rhine bridge at Arnhem. The plan hoped to end the war in a matter of months, but as was bound to happen with a plan of such complexity…a few things went wrong.

Market-Garden was the brainchild of Bernard Montgomery and was an uncharacteristically bold plan for the normally cautious Field Marshall. Up to this point paratroopers had had limited success in World War II. The first major operation to use paratroopers was Germany’s near disastrous (only luck and allied incompetence prevented defeat) invasion of Crete where the world learned the folly of dropping unsupported paratroopers into “hot” landing zones. The allies utilized paratroopers to greater success (though on a smaller scale) in the amphibious invasions of Sicily and Normandy. However, the key to the success of both of these cases was the close naval support of the paratroopers.

So, with D-Day almost 3 months gone and the allied advance having ground to a halt (basically they had outdistanced their supply trains after foolishly not taking the port city of Antwerp before moving on) the idea of a large scale independent paratrooper operation was once again put onto the table. It is important to keep in mind here that paratroopers were a “weapon” new to WWII and finding a way to put them to use was quite appealing. What commander wouldn’t want to be able to drop a division or two anywhere he wanted no matter where the front lines were? Thus planning for one of the most daring operations of WWII began.

There is a saying that says something along the lines of “in war, no plan should have more than one risky element” (does anyone know the quote I’m thinking of? Anyway I might not even be close…but I think it goes something like that…) Operation Market Garden seemed to be almost entirely risky elements. If even one bridge was unable to be secured the whole operation would be compromised. The paratroopers would be operating unsupported deep within enemy lines, and, as paratroopers, would only be lightly armed with little ammunition should the engagement drag out. The British 1st Airborne was meant to hold the furthest bridge at Arnhem for at most 48 hours which left very little time for the XXX Corps armored vehicles to traverse the 60+ miles of narrow, often raised (making them easy targets) highway from the allied front lines to relieve them. Everything had to come together perfectly, but perfectly so rarely happens once a plan is set into motion. Let’s take a look at the allied setbacks:

- To start, the German resistance throughout the operational area was thought to have been mostly old men and Hitler Youth, but as it turned out, two (admittedly extremely battered) panzer divisions had been reassigned to Arnhem for rest and refitting, a major obstacle as paratroopers did not have nearly the antitank support needed to deal with the German armored divisions. There was evidence that the Panzer divisions were in the area, but higher ups chose to ignore the warning signs.

- In what was to be in retrospect one of the major failures of the operation, the allied paratroopers dropped miles from their target bridges. In the case of the 1st Airborne at Arnhem, they were dropped 6 miles to the west of their intended bridge with only Lieutenant-Colonel John Frost’s 2nd Battalion finally reaching the Arnhem bridge with the rest of the 10,000 men to eventually land in the area getting tied up in the city itself in what became named “The Devil’s Cauldron” (from which only 2,000 escaped…operation Market Garden had more casualties than the entire D-Day invasion put together).

- Two teams of American radio operators had landed with the 1st Airborne but the radios were set to the wrong frequencies. This and other radio problems left the entire division out of radio contact with any other parts of the operation until the last day of battle. There was thus a lack of close air support and after losing their drop zones to German resistance they had no way of alerting their resupply planes that they were delivering all their supplies to the Germans.

- With various resistance movements having been compromised in the past, the allies did not work with the Dutch resistance movement. If they had they might have been alerted to any number of things, the most ironic being the fact that the dutch telephone system was working all throughout the area which could have saved the communicationless 1st airborne a great deal of trouble. Resistance could have also alerted the 1st airborne to the existence of the Driel Ferry which could have transported troops to the south side of the Rhine from the first day.

- German 88s at Zon delayed troops long enough for them to blow the bridge there causing a major delay as bridging equipment was set into place. This was just another reason the XXX Corps ended up running so far behind schedule on their sprint towards Arnhem.

- Top secret plans for the whole operation were inexplicably taken onto a glider which was subsequently shot down and recovered by the Germans. Luckily the Germans took the plans as fakes stating that if the bridges were the real objectives, why would the allies set their drop zones so far away?

- Poor weather was in effect for almost the entire operation (aside from the first day) hampering most of the air operations. Major-General Stanislaw Sosabowski’s Polish brigade didn’t even get to enter the battle until day five due to fog.

- The Nijmegen bridge (the last bridge before the final Arnhem bridge) was strongly held by the Germans (partially because the 101st’s delay in reaching the Arnhem bridge let the Germans through to reinforce the area) causing even more delays as the 82nd waited on boats to make a dangerous river crossing of the Waal which would come to be known as “Little Omaha”. Into withering machine gun and artillery fire (with the preliminary allied smoke screen being blown away in the wind) roughly 400 men paddled (with helmets and rifles due to lack of paddles) the 500 feet across the river (losing half their numbers in the process), stormed the machine guns and finally took the bridge on the fourth day.

- Frost’s men (roughly 700) had heroically held the Arnhem bridge for four days, twice as long with a fraction of the manpower as they had been expected. But with ammunition finally completely gone (some men were down to fighting with knives) they were forced to surrender their hold on the north end of the bridge at the end of the fourth day.

- XXX Corps waited 18 hours after capturing the Nijmegen bridge before heading towards Arnhem during which time the last of Frosts men were cleared from the Arnhem bridge and southern defences were shored up all around Arnhem. It was a controversial decision, but tanks without infantry support would have been sitting ducks on the raised roads that led to Arnhem.

The number of setbacks seem enormous, but in an operation where everything needed to go right, perhaps they were about as lucky as they could expect to be. Nine days after the first paratrooper landed the remaining men of the 101st were finally evacuated from the “Devil’s Cauldron” that the suburbs of Arnhem had become. Operation Market Garden became the last major allied defeat of the war (since I wouldn’t count the Battle of the Bulge as a German victory).

Many things went wrong, but I’d say the biggest single drawback was the presence of the 9th and 10th SS Panzer division, which, even in their damaged state (between the two divisions was only a company of tanks) were still able to outclass the paratroopers whose best artillery support were the “quite unlethal” 75mm pack howitzers. This combined with the slow progress of the XXX Corps due to the narrow road and bridge setbacks along the way ensured that the city was firmly in German hands by the time they made it to within a mile of Arnhem.

The appealing idea of the “independent” parachute division was finally shown to be unfeasible in Operation Market garden as the allies never tried another major airborne operation without close non paratrooper support, and indeed, after the war the demise of independent paratroop forces was a direct result of lessons learned in operation Market-Garden.

4 Comments

The Allies were terrible about dropping paratroopers far off the mark. Granted, it was a new deployment technique typically attempted under less-than-ideal conditions, but still…imagine how frustrating that had to be for the combat soldier.

Aside from the knee jerk reaction in the opposite direction from Crete (where they dropped right on top of the combat zones), part of the problem in Market Garden was that there weren’t really any good drop zones close to Arnhem. Directly south of the bride was spongy polder that prevented glider landings while north were heavy flak emplacements. Still, I’m sure they could have found something a bit closer…I’ll have to check the map to my detailed 600 feet to the hex monster (16 foot map) wargame of the entire operation and see what could have been better.. 🙂

My Dad was one of the 10 American radiomen attached to the British First Airborne. They did everything they could do. The crystals were set to the wrong frequency in England. That haunted him until the day he died.

my father was in the british first airbourne was captured and sent to pow camps. He got right up to the main bridge He never got over that battle. He lost a lot of mates. He had one of the invasion maps. I think there were only 3. He past away 5years ago.