It is astonishing how different Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu: Phantom of the Night is from Murnau’s classic silent horror film considering it is an almost scene for scene remake. To be sure, both versions share the fixation with the natural world, the inhumanity of Dracula, and the underlying sense of terror and dread. But Herzog’s version of Dracula (the true heart of both films) is painted as more of a lost, forgotten sad spirit than the creeping juggernaut of evil and destruction that was Murnau’s version of Dracula. He is not human, but some part of him longs for those things humanity has which are denied to him. While this arguably makes him less terrifying overall, it also adds a welcome degree of complexity to his character.

Herzog may not quite be the finest director ever (though he is certainly up there), but his command of landscape is unrivaled and thus he was well suited to remake Nosferatu. From Jonathan’s journey to Dracula’s castle to the final shot of windswept plains, Nosferatu is full of unparalleled images of natural beauty. Landscape is very important to Nosferatu, for Dracula is a primal force of nature, and the extended shots of waterfalls and time lapse clouds (there is a great part on the commentary where Herzog explains that they were up in the mountains for a few days taking the time lapse footage and “yodeling and singing Bavarian folk songs”) help underscore this idea.

The music by the Herzog standby Popol Vuh is expertly incorporated into film as well. As the landscape turns more menacing the closer Jonathan gets to Dracula’s lair, the music too switches from a relatively upbeat, almost pop sounding soundtrack to forlorn choirs and epic Wagner selections.

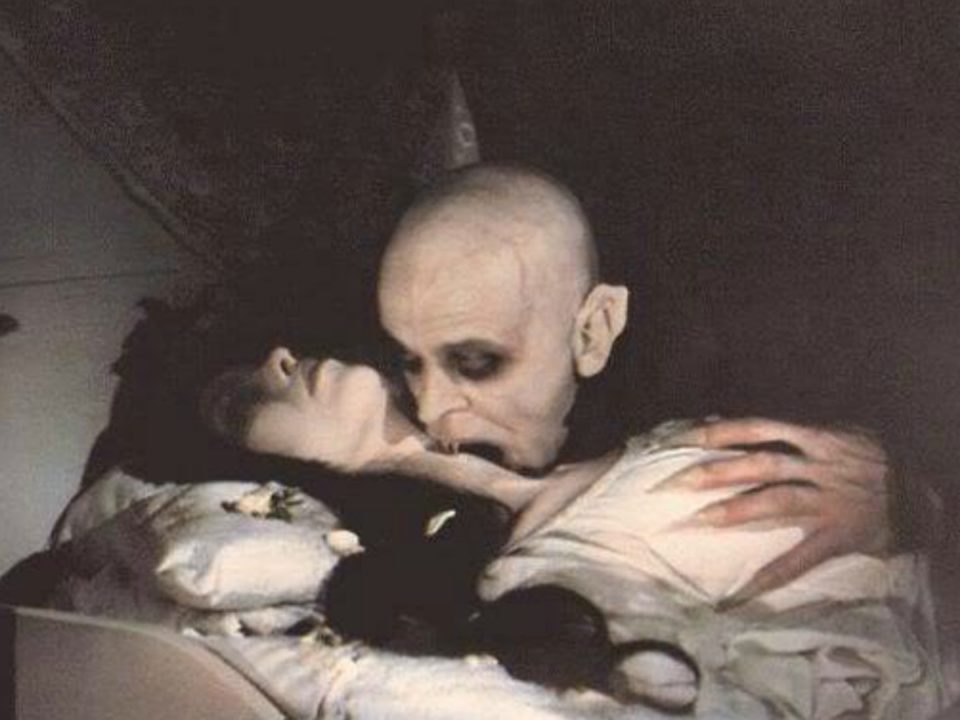

This is Dracula’s film however, and Klaus Kinski as the count does an impressive job of holding the viewer’s attention by matching the power of the landscape and score (not that I would expect any less from him). I talked a great deal last week about how the Dracula from the silent version was such a demonic inhuman beast that was completely alien to humanity. Herzog’s Dracula, however, does not exist solely to destroy all that is good and human in the world. He is a monster to be sure, but a monster who has seen what is good about humanity and longs to experience such things as love and companionship himself. He might not truly understand these concepts, but he desperately longs for them to break the pain of his solitary existence.

This is an interesting move to make. By humanizing Dracula you risk losing some of the terror a truly otherworldly beast (as in the silent version) inspires in the viewer, but it is a fascinating concept in its own right. Is there anything more wretched than an individual who can find no happiness in the life they have chosen to lead? And in Dracula’s case, it is not even a choice, he must forever be a creature of the night, a beast who preys on humanity; after finding himself unhappy there is no end to his existence.

But Herzog knows better than to let pathos ruin the character’s menacing terror and you find out what he is up to when Dracula tells Lucy he will give her her husband back if she will give him just a tiny bit of the love she has for her husband. The viewer slowly realizes that this creature of great power does not understand the basic nature of what he longs for. Where just seconds before the viewer felt sympathy as Dracula explained that “the absense of love was the most abject of sufferings”; that feeling turns to revulsion as they come to realize it was merely a mask of humanity that this bestial creature was wearing.

Thus the viewer’s image of Dracula plunges into an abhorrant “uncanny valley” where his inhumanity is in actuality more pronounced because of his “human” desires. In the silent version Max Schrek was a Dracula like no other and to look into his eyes was to see something that did not belong in this world. It was a triumph of filmmaking to capture something like that, and here, against all odds, Herzog has equalled Murnau’s feat by creating a Dracula that was just as unsettling and yet at the same time far more complex. Like the thought of a monstrous spider holding a small child in its hairy legs, Herzog’s version of Dracula will unsettle you the longer you think about it.

4 Comments

“He is not human, but some part of him longs for those things humanity has which are denied to him.”

I’ll be honest – I was pretty much reading this entire post looking for a way to make an HSM joke. Give me a couple days – maybe I’ll come up with something.

Well from the bits and pieces of HSM I’ve seen, I’d say it seems to inhabit its own kind of “uncanny valley” with regards to the aproximations of humanity represented by its characters…

i´m wondering if this movie is a copy of the first dracula movie

It’s a very close remake of the 1922 silent version…it doesn’t have quite as much to do with the 1931 film Dracula (though they are all the same basic story).