First, if you haven’t seen Casablanca and don’t know how it ends…well lucky you! Quit reading this and go watch it! If you have seen it, or don’t care about spoiling one of the great movies for yourself, read on:

Casablanca is one of those movies that just gets better with every viewing. It pretty much exemplifies everything that was great about the “Hollywood classics of the 30’s and 40’s”. Yet, while I wouldn’t change a single thing about the movie, every time I watch it I can’t help but think “Fuck Lazlo, get on that plane with Ilsa Rick!” Of course, Casablanca is a film about a man and a woman who sacrifice their love for a greater cause. Rick learns there are some things worth sticking your neck out for, and to change the ending would change the entire film.

However, just because the ending works for the movie, it doesn’t mean it was the right choice. Let’s look at the details. Rick knows that the only way the resistance leader Lazlo will leave Casablanca to continue his fight against the Nazis is if Ilsa goes with him. Rick has also decided to join the fight himself, which would probably also be in a resistance capacity since America had not entered the war, and almost all of Europe except England had capitulated.

So, the question becomes, just how effective was the French resistance (and resistance/espionage movements in general) at stopping the Nazi war machine? If it turns out to not have amounted to much more than a hill of beans, then Rick “may have made a big mistake”.

The first and most basic problem with resistance movements in Western Europe was that the terrain was unsuited for partisan guerrilla actions. Flat countryside and vulnerable civilian populations were not conducive to a successful resistance force. And yet the necessary rough terrain could not sustain any kind of army, thus external supply was needed as well. Only in the case of Yugoslavia and in Russia’s Pripet Marshes was any meaningful military resistance able to exist and be supported from without.

The three largest partisan uprisings, in Vercors, Warsaw and Slovakia turned out to be massive failures that resulted in hundreds of thousands of civilians being murdered in reprisals. Taking a closer look at the French example, Vercors, on July 14th the allies had air dropped a thousand loads of weapons and ammunition to the several thousand resistance fighters at the plateau of Vercors. In response the Germans isolated the plateau, landed SS troupes by glider and killed every single person they found there. Warsaw and Slovakia were much worse (as many as 200,000 civilians were killed in Warsaw alone).

Even in the seemingly successful cases of Russia and Yugoslavia, the success of the partisans was flawed. Looked at with hindsight, these “resistance success stories” were actually of limited significance.

The large pockets of Russian soldiers that had been surrounded in the impenetrable Pripet marshes were successful in operating independently against the German occupiers once they began to be supplied by Stalin. Though, modern estimates of their success suggest only around 35,000 German soldiers killed, which is a paltry sum compared to the exponentially greater number of men, women and children killed in reprisals.

The quick capitulation of Yugoslavia left a large portion of its army armed and governmentless. Supplied by the allies from without, they (along with their leader Tito) became the shining example of successful partisan resistance after the war. Yet, in hindsight, they were never able to successfully be more than a thorn in the German side; it was only with the arrival of the Russian troops that Yugoslavia was finally liberated.

Even in the best of cases, the Resistance in Europe failed to have any meaningful effect on drawing away from the front line troops. Of the 300 divisions (a late war German division was probably around 10,000 troops) deployed across Europe on D-Day, fewer than 20 were devoted to internal security. And of these, they were mostly low quality, “expendable” troops (of the 13 divisions in Yugoslavia, only one was first class). And aside from the “trouble” areas, the security troops were even more minimal. In Lyons, the second largest city in France, there were only 500 security troops (out of the total of only around 6500 devoted to French internal security in contrast to the estimated 116,000 armed French resistance fighters).

So, if resistance movements were largely unable to have any meaningful effect on the German war machine in even the best of cases (and in all circumstances caused far more civilian casualties than German troop losses), then did they actually matter at all?

While there were some examples of successful non-military resistance operations (like when the Norwegian resistance fighters destroyed the heavy water plant at Vermork–effectively ending the German atomic weapons program*), again, the overall effect of sabotage and assassinations was somewhat underwhelming.

The primary effect seems to have been a psychological one. The very idea of a resistance movement, fighting for freedom was enough to sustain national pride and keep the spirit of a Europe under the heel of a Nazi jackboot from utter despair**. Underground papers and radio broadcasts were great sources of hope (even though many fell into and continued to operate under German hands) to the Europeans living under occupation. Even something as simple as a workers strike let the people of Holland (for instance) feel less helpless in the face of the atrocity around them (though in the case of the Dutch strikes, the Germans simply quit supplying them with food and coal for the winter causing a great number of deaths from starvation).

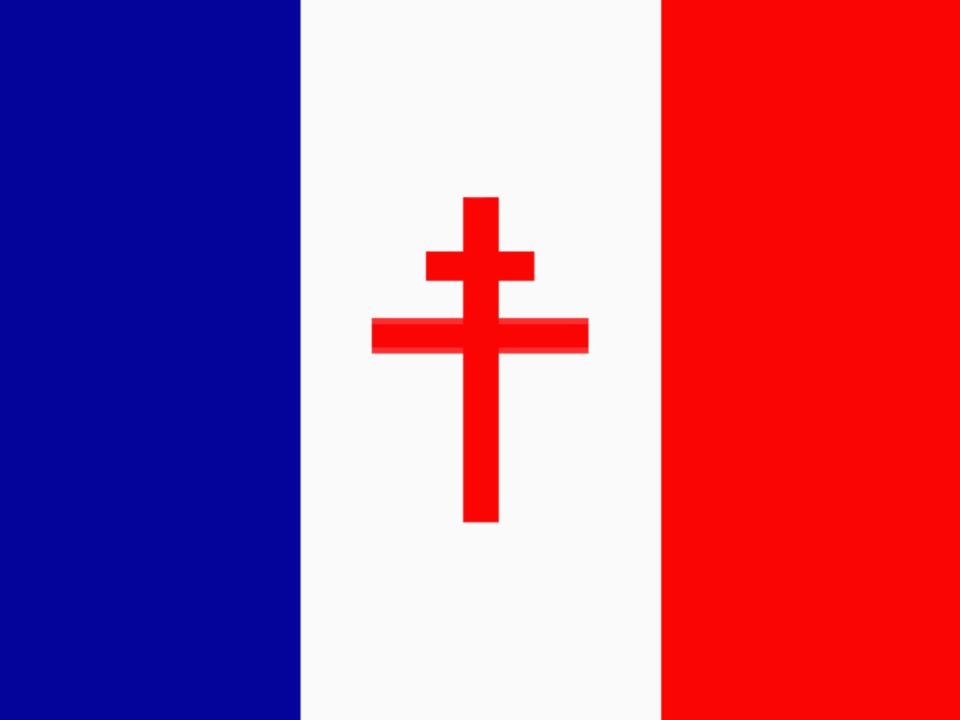

So, with that brief look into various facets of the resistance movements in World War II, do I still think Bogart’s character made the right decision in sending his girl off with the famous resistance symbol? Well at that point in the war, when things looked most bleak for the world and America had yet to enter the war, symbols like Victor Lazlo were what was needed to galvanize the line toe-ers to action. Lazlo was not just a powerful symbol of resistance, but supposedly also an eloquent writer. If anyone in the resistance was needed, and if ever one person could make a difference it was him.

On the other hand, there were plenty of other resistance fighters, one person really can’t make much of a difference, and true love seems a little more important than the fate of the world (that’s what you get for asking a romantic nihilist), so I stand by my first thoughts. Rick and Ilsa should have gotten on that plane!

Oh, and if it had been Lauren Bacall instead of Ingrid Bergman playing Ilsa, I wouldn’t have had to write this post, the answer is obvious–of COURSE you get on that plane!

* A “Quite Interesting” side note on the German atomic weapons program was its potential when combined with the ballistic missile. Amazingly, in 1944 the Germans were actually firing true ballistic missiles (their V-2 rockets) at London and were in development of a new missile called the A10 which would have a range of 2800 miles (sufficient to reach America) and would carry a nuclear warhead as its payload. The allies had no way to prevent such a super-weapon. Luckily the Nazi nuclear weapon program was still years from developing an atomic bomb by the time the war ended. But just imagine…a pilotless nuclear weapon that could fly halfway around the globe in 1940’s. It is amazing the leaps and bounds weapon technology will take during times of war.

** A second “Quite Interesting” side note that is only marginally related is the German response to resistance fighters painting “V” (for victory) all over their cities. Goebbels had posters made explaining that “V” stood for “GERMAN victory over all of Europe”. Efficient Nazi thinking at its finest, brilliant! 😉

Comment

[…] discussing his work on The Pacific. While the geography of countries like the Netherlands and France made it tough to mount successful guerilla campaigns against occupying forces, the geography of […]