All-timer classic Hollywood director Howard Hawks LOVED to re-use elements from his movies. Whether it was to mine Bringing up Baby to produce the superior Man’s Favorite Sport (yeah, superior, I said it!), or whether it was to simply write the same ballsy dame that reminded him of his second wife into every single one of his movies, Hawks was no stranger to pillaging his oeuvre. The most notable example of this was the trilogy of late-period Westerns he made that all had the same basic “bad guys besiege a Sheriff and his ragtag band of professionals” plot.

The first of these films, Rio Bravo (1959) is arguably Hawk’s greatest Western…as well as Hawk’s greatest film, as well as the greatest film of all time ever. Really, it’s about as good as movies get even if it’s a rambling bit of populist fare with a couple of goofy singers as costars. The final film in the trilogy (and Hawk’s final film as well), Rio Lobo (1970), is (rightly) panned as a failure. Today I’d like to look at the middle film, 1967’s El Dorado, a Western that is usually considered good, but one that also lives in the shadow of its monumental forbearer Rio Bravo.

My first question is “why remake your own movie multiple times?” Was it a creative self-challenge? Was Hawks simply out of ideas? Or was Rio Bravo simply a huge success (for a western that is–it wasn’t even in the top ten for highest grossing films in 1959, and it was knocked out of first place by Some Like it Hot after one week) and the studio/Hawks saw $$$ in a remake, even only 8 years later. My guess is all 3 were factors in the making of Rio Bravo. The pantheon of immortal American directors of Westerns never took themselves too seriously, so Hawks would have never made a movie simply as a “creative exercise,” but he was too goddamn good to keep from subconsciously rising to the challenge of staying fresh in stale territory anyway. He was also too good to be completely out of ideas, but I’m sure there was some comfort in sailing in familiar waters as his career wound down. Bottom line, the studio was more than happy to have another Rio Bravo to distribute, and Hawks was happy to mold another masterpiece from familiar elements.

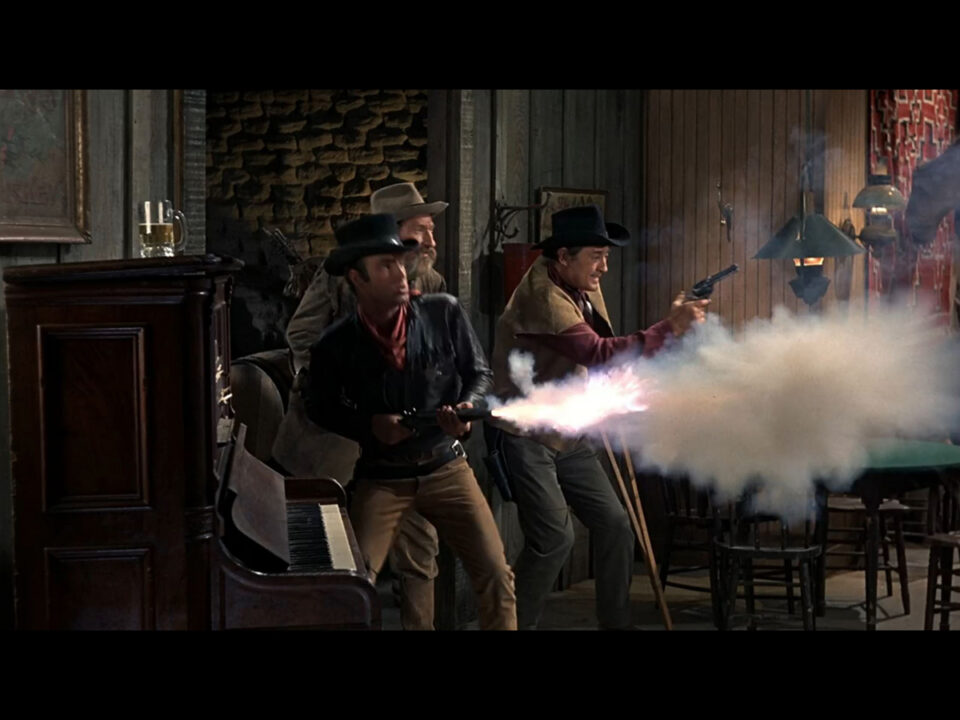

At first, El Dorado seems to be a very different film. Wayne is a wandering gunslinger with a code who gets shot close to his spine (leading to an interesting injury angle for the rest of the film). The characters all have analogs though–the puffy eyed laconic best friend is Robert Mitchum this time (who nearly steals the movie, but not quite–this is John Wayne after all), the hot shot kid is James Caan in a funny hat (who carries a sawed off shotgun in a leg holster since he can’t shoot straight), and the old coot is Arthur Hunnicut (he’s fine, but is the only downgrade in casting from Rio Bravo as no one was going to be able to top Walter Brennan’s “Stumpy”). The plot rambles a bit before settling back down in the original town 10 months later with Mitchum a drunk, and Wayne, Caan, and Hunnicut bunkering down for a series of increasingly familiar set-pieces.

Like Rio Bravo, (and most of Hawk’s late-period work) El Dorado has a real laid-back vibe. Supposedly, after chucking half of Leigh Brackett’s original script and deciding to just do Rio Bravo again “if the audience liked it the first time, they’ll like it this time” Hawks ended up keeping true to his original pitch to get Mitchum on board: “no story, just characters.” The approach was even improvisational at times with whole scenes being constructed on the fly, comedy bits added, recurring gags expanded upon until eventually El Dorado took shape in the cutting room as one of cinema’s greatest acts of offhand genius.

And the characters really do shine. The performances are lived in and endlessly interesting. There is a real delight just seeing the characters bounce off of each other, letting the zingers fly (I suspect Brackett had more to do with the script than she let on). I really want to know more about Bull in the Indian Wars, or about Mississippi’s mentor, or about how Wayne and/or Mitchum saved each other’s lives. These characters and the world they live in feel far deeper than the surface level treatments you see in lesser films.

El Dorado was a modest success on release, but critics also derided it for being an out of touch old man’s movie (for reference, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly came out a year earlier)–and they weren’t wrong, El Dorado WAS a throwback. But take it from this lover of classic Hollywood westerns, they don’t get much better than El Dorado. To borrow a quote from Stumpy in the previous film…”it’s a good’un!”

Leave A Reply